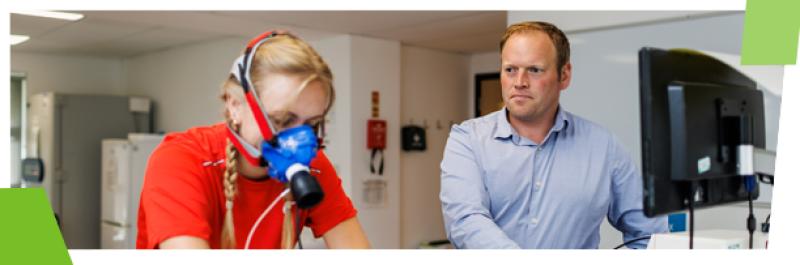

When making resolutions for the new year, individuals often prioritise improving physical health or mental health, but rarely consider how one can affect the other. Dr Pascal Burgmer, a social psychologist at the School of Psychology, explains why we should be considering how to look after both body and mind to optimise health and wellbeing. He said:

‘Should we be focusing on a new diet and a new exercise regime to get in shape during the Covid-19 lockdown? Or should we finally download that meditation or mindfulness app and start training our mental muscle? Research at the intersection of social psychology and philosophy suggests that it might be helpful to consider how body and mind are interconnected, rather than focusing on one over the other.

‘People have different viewpoints on how minds and bodies are related to each other, and we can reliably measure these lay beliefs and relate them to important outcomes such as health-related attitudes (e.g. “regular exercise is important”) and behaviours (e.g. picking a salad instead of a burger for lunch). Specifically, it seems that those who tend towards a more dualistic construal of mind and body display less positive health attitudes and behaviours. In other words, viewing the mind as independent from the body decreases our motivation to take care of the latter. One of the reasons for that is that believing that the two are independent from each other entails the view that mental wellbeing does not require physical health.

‘Going back to making resolutions, one implication of these findings is that it should be helpful for us to think about how our minds are connected to our physical bodies, and how taking care of the latter will also boost wellbeing of the former: a sound mind in a sound body. Thinking of the mind – and our conscious experience – as grounded in physical matter can help us to draw a connection between eating healthy and exercising not just to be in shape, but to feel better.

‘However, all of this is not to say that mind-body dualism must always be a bad thing. In fact, viewing the mind as separate from the body might assist us in times of coping with existential psychological threats such as fear of death or physical injuries. We might detect a few new wrinkles when looking in the mirror, but that does not automatically mean that we must also feel older. Nevertheless, thinking about both mental and physical wellbeing as connected can be a first and important step to make resolutions that reflect our complex nature as organisms with both a physical body and a conscious mind.’