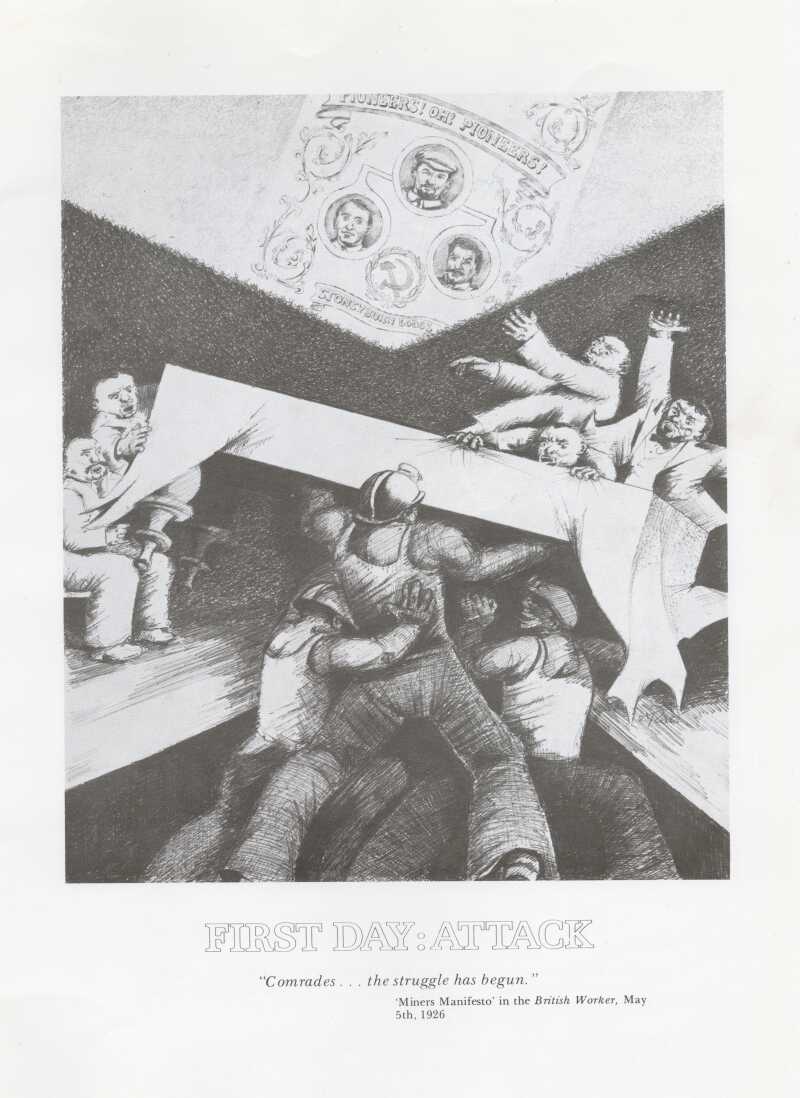

1926 General Strike

The 1926 General Strike lasted nine days from the 4th to 12th May 1926, the product of a turbulent era for industrial and economic action. It was called by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to defend the pay and conditions of coal miners. Although the official strike itself only lasted nine days, it saw miners under striking conditions for almost six months.

Mine owners wanted to maintain profits even during the times of economic instability, and this took the form of wage reductions and longer working hours. The strike was a sympathy strike, which meant that many workers from other industries went on strike, not just miners. Striking numbers were estimated to be around 1.5 million.

From The Generals’ Strike: 20 Drawings by Andrew Turner. London: The Journeyman Press. 1977

(Richardson Mining Collection , Box 7)

There were several days of unrest across Britain, but the strike ended on 12th May 1926. The TUC agreed to end the strike, although without any guarantee about worker victimisation.

The miners continued their resistance for a few months

afterwards, but due to economic circumstances, most returned to work by

November 1926.

In 1945 the government announced its intention to nationalise coal mining, introducing the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act 1946.

1972 Miner's Strike

The 1972 Miner’s Strike took place from 9th January to 28th February 1972. The strike was called as a result of a pay dispute between the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the Conservative Government under Prime Minister Edward Heath. The strike ended when the miners accepted an improved pay offer.

The nationalisation of the mining industry in 1946 did improve the working conditions and wages of miners. However, miner’s wages had not had kept pace with other industries and declined significantly through the 1950s and 1960s. This coincided with widespread pit closures throughout the 1960s.

Advertisement for a Spiralarm Coal Miner’s Gas Lamp in the book National Coal Board: The First Ten Years.

This strike was the first official strike for miners since the 1926 general strike. Flying pickets and mass picketing were popular tactics during this strike, with miners attending other industrial sites to encourage support and disrupt the transport and movement of coal.

An example of this was at a fuel storage depot near Birmingham which was

the site of a mass picket, becoming known as ‘The Battle of Saltley Gate.” The number of strikers at this

picket successfully closed the depot.

1974 Miner's Strike

Despite the success of the strike in 1972 and the acceptance of a pay offer, pay conditions for miners worsened over the following years. In late 1973, the National Union of Mineworkers rejected a pay offer and implemented a ban on miners working overtime. This had a severe impact on production of coal, and led to Prime Minister Edward Heath introducing a Three-Day Working Week to help reduce the consumption of electricity.

When further pay negotiations failed, in January 1974 a strike was called by the NUM, and miners went out on strike from 5th February. The strike was well supported by miners, and the NUM made greater efforts to control the violence on the picket lines that had been a feature in 1972.

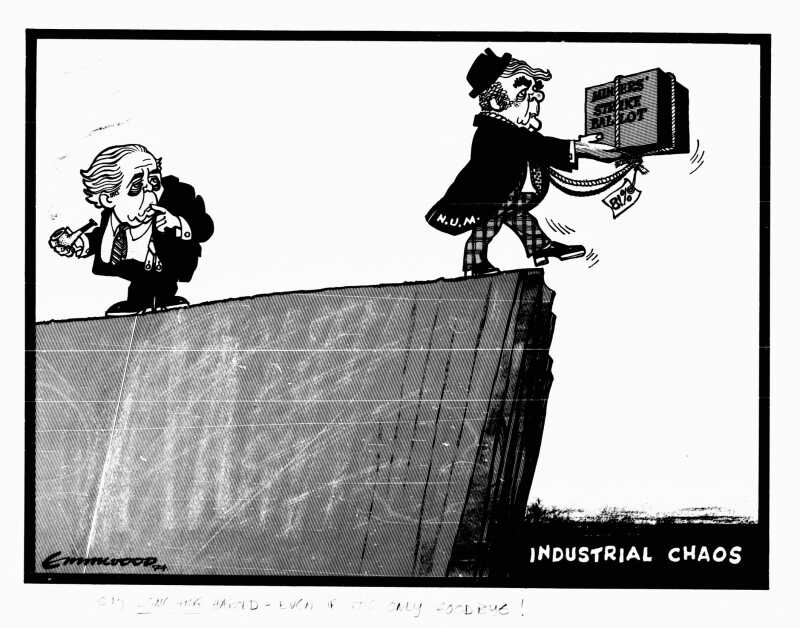

"Say SOMETHING Harold - even if it's only goodbye!" - Emmwood [John Musgrave-Wood], Daily Mail, 5th February 1974

Within two days of the strike being called, Edward Heath called for a General Election. His expectation was that the public would support the Government and not the miners. Ultimately, his plan failed, and the Government lost the General Election, which led to a minority Labour Government under Harold Wilson.

A 35% pay offer was quickly accepted by the miners and the strike ended. The strike was seen as a huge success for the miners and for the British labour movement.

1984-1985 Miner's Strike

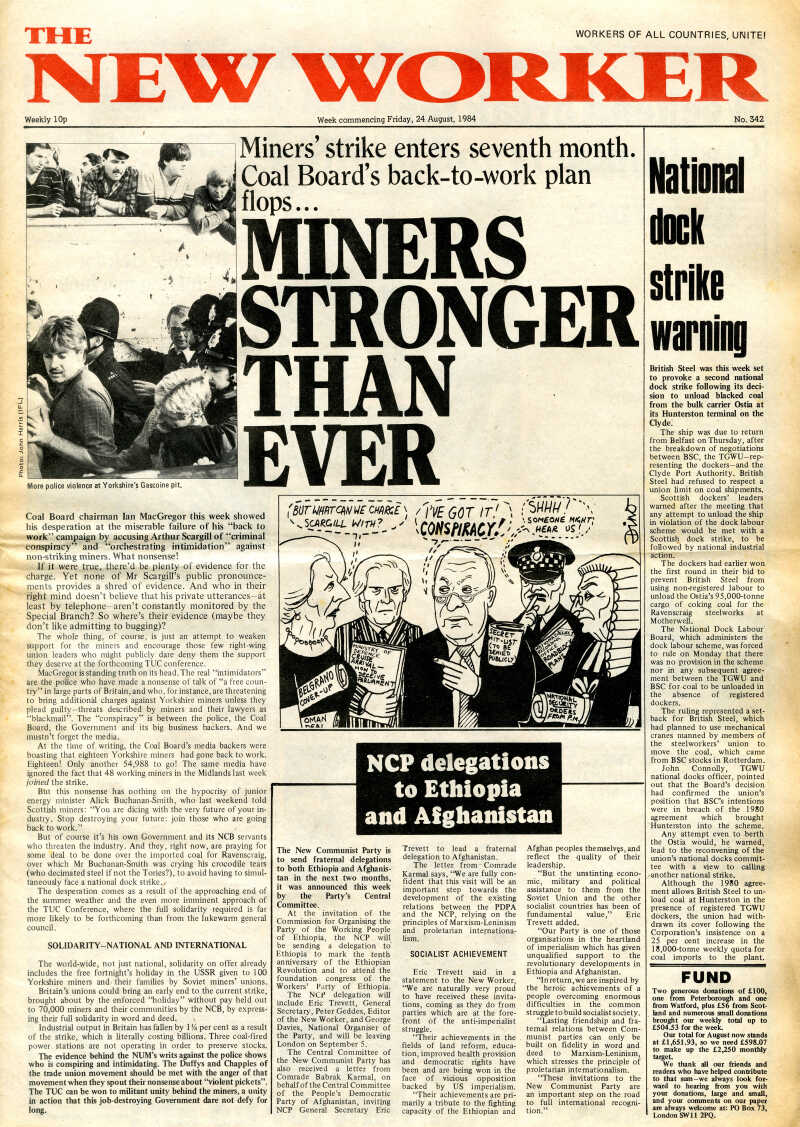

The 1984-1985 Miner’s Strike was a significant and bitter dispute between the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) under their President Arthur Scargill, and the British Government under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

The dispute focussed on the closure of mines and the impact on the livelihoods and communities of Britain's coalminers. The National Coal Board (NCB) announced a plan for the widespread closure of pits on 6th March 1984. Using the success of the 1972 Strike as a model, the NUM planned to cause a shortage of energy due to a lack of coal supply.

Front page of The New Worker newspaper, 24th August 1984.

This plan was thwarted by the actions of the government who built up coal stocks in preparation for the strike. Other government tactics included using police to prevent the flying pickets that had been so successful in the 1972 strikes.

The strike was characterised by the bitterness of the dispute, the violence on the picket lines and the legalities of the national ballot called by the NUM. The strikes are also known for the key role of women in supporting the strikes and the impact of this for their future lives.