Coal mining in Britain has taken place since 1840, but also dates back in Europe to 1500. Coal mining was not seen as advantageous until the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century after which it was used to power steam engines, heat homes and generate electricity.

In 1856 the successful mining of coal in France inspired a proposal to try coal mining in Kent. This involved deep shaft mining which hadn’t been seen in Britain before and led to the development of the Kent Coalfields in the early 20th century.

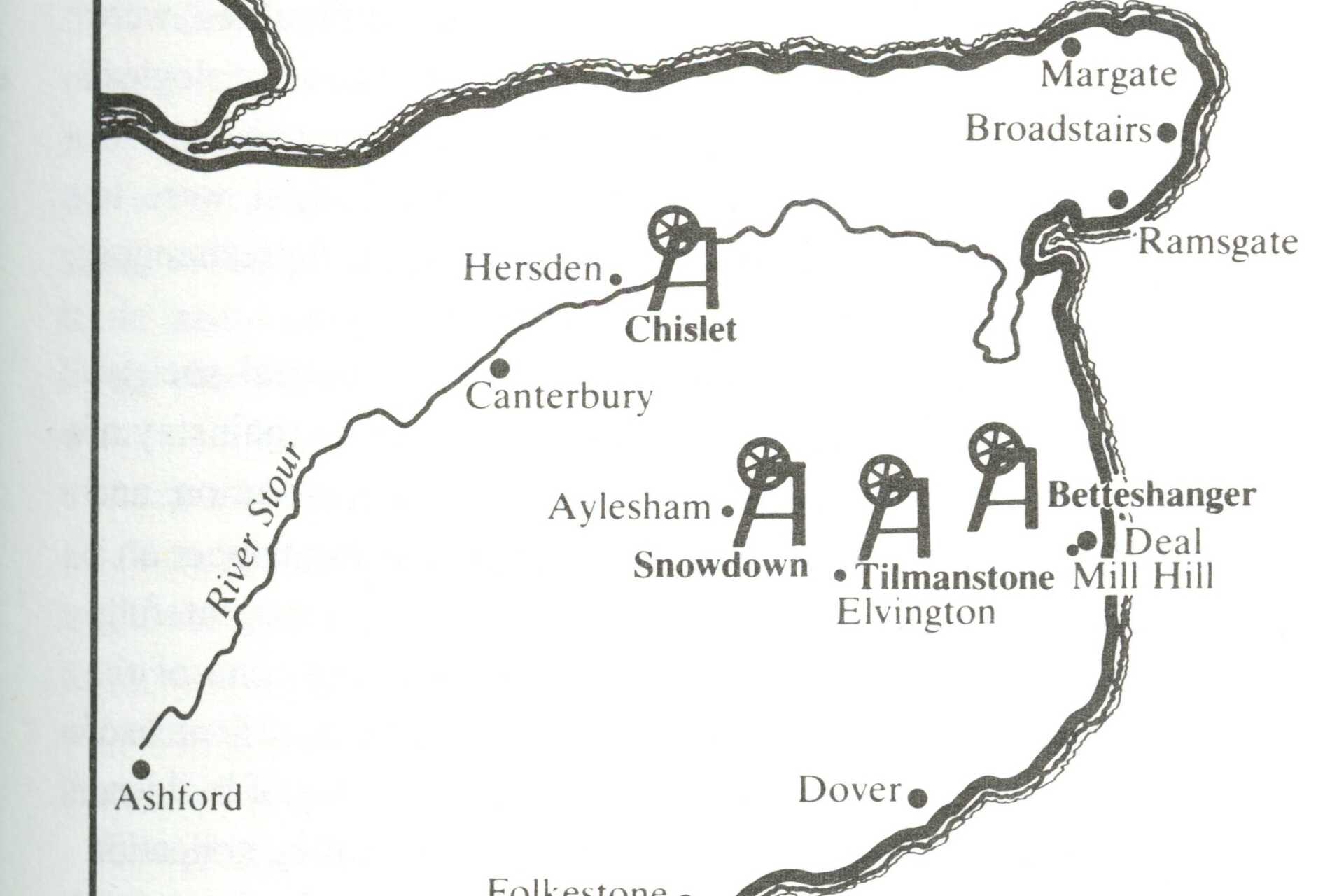

The first site to be explored was Shakespeare Colliery at Shakespeare Cliff near Dover. However, the site was soon closed in 1915 due to poor coal and conditions. Coal mining in Kent expanded rapidly from here onwards, with new sites tested and several collieries established. Around ten collieries were opened in this period but, in the end, only four produced any coal.

Coal mines in Kent were some of the deepest in Britain as the richest seams of coal were found at these depths. This deep mining meant that conditions in Kent mines were exceptionally hot.

Pockets of water in the ground meant the mines were also prone to flooding. This often delayed the production of coal, and caused several fatal mining accidents.

Betteshanger

Betteshanger, near Deal, opened in 1924 and became the

biggest Colliery in Kent. It first produced coal in 1927 and had an initial

workforce of 1500 miners, most of whom came to work at the mine from outside

the area. Betteshanger was the last to

return to work after the 1984-1985 miner’s strike and the last mine in Kent to

close, finally ceasing production in 1989.

Chislet

Chislet, near Canterbury, was one of the first sites to be explored after the war in 1914. Coal was first produced at Chislet after 4 years in 1918, at 411 meters. The colliery was modernized in 1947, but felt the impact of the demise of the steam railways in 1968, and closed in 1969. The mining workforce transferred to the other Kent collieries.eaders

Snowdown

Snowdown, situated between Dover and Canterbury, opened

in 1907 but flooding impacted the sinking of the first shaft, and in one

incident 22 men lost their lives. Coal was finally reached in 1912. Snowdown,

often called Dante’s

Inferno, was the deepest, and hottest, of

Kent’s mines, as coal was mined at a depth of 911 meters. The village of Aylesham was built

in the 1920s to accommodate the mining workforce. The mine closed in 1987.

Tilmanstone

Tilmanstone, near

the village of Eythorn, was opened in 1906, although coal was not produced

until 1912. Like other Kent mines the

colliery had problems with flooding and the economic production of coal. The

company that owned the mine went into administration for a time in 1914. In the

1920s, Tilmanstone built an interesting

ariel ropeway to transport coal to Dover Harbour. The mine was

closed in 1986.

This outline map shows the location of the four main producing coal mines in Kent: Chislet, Snowdown, Tilmanstone and Betteshanger.

The mining day is divided into three parts : mornings, afternoons and nights. Each part is called a shift.

The first shift of the day begins at 6am, but for the miner’s working that shift their day may begin much earlier. For example, miners might need to get up at 4.30am in order to get to work in time for the first shift. Many miners walked several miles to work before car ownership became widespread.

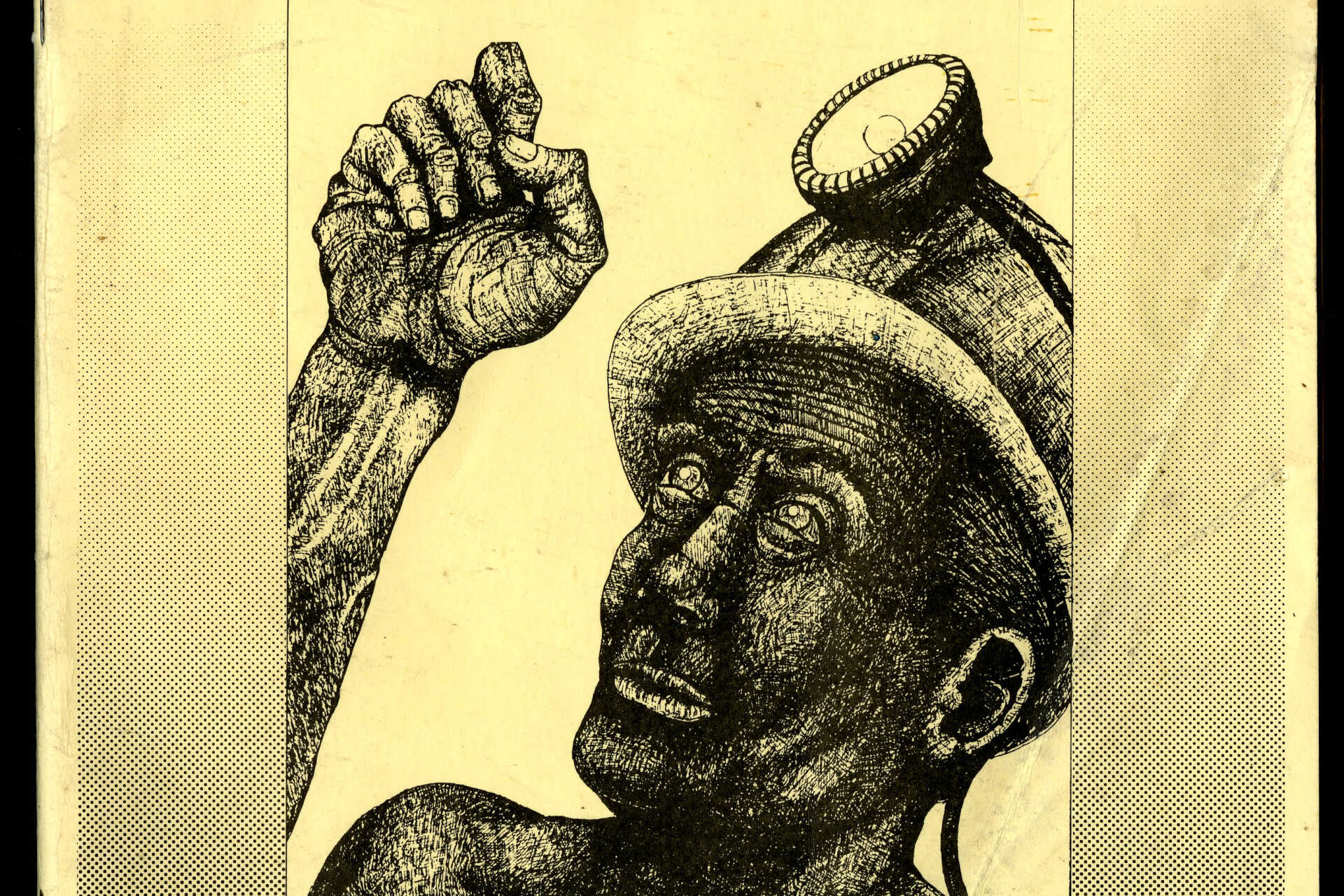

Before he started his shift the miner would get changed into his ‘pit clothes’, stored in his ‘dirty’ locker. The clothes he arrived in would be placed in in his ‘clean’ locker. They would then travel down the mine shaft in the lift ready for the start of their shift. Payment only began when they reached the ‘coal face’ and ended when they left. Once in the mine the miners did not return to the surface until the end of their shift at 1.45pm – they took all their breaks and ate their ‘snap’, kept in an airtight snap tin, whilst down the mine.

The second shift of the day started at 2.00pm and followed the same pattern. Arguably the hardest shift of the day was the night shift, which began at 10.00pm.

Each miner was issued with two metal ‘checks, bearing the number allocated to him’. They would hand one to the banksman at the start of his shift. At the end of the shift he would hand in the second check to the banksman. The Banksman was able to account for who was in the mine at any given time.

Image reference: From Support Sacked and Imprisoned Miners Booklet, Richardson Mining Collection. Box 6

The Kent coalfield was the last to be developed in the UK, which meant Kent’s first miners migrated to the county from more established mines in the early 20th century. This included Wales, Yorkshire, Durham, Newcastle and Scotland. This made the mining communities in Kent hugely diverse in terms of geographical histories, dialects, and customs.

“In the 1930s, Billy Marshall, Betteshanger branch secretary, had to ask the chairman to translate some of the contributions from the floor so that he could keep the minutes”

Malcolm Pitt, The World on our Backs: Kent Miners and the 1972 Miners’ Strike. Lawrence and Wisheart Ltd, 1979.

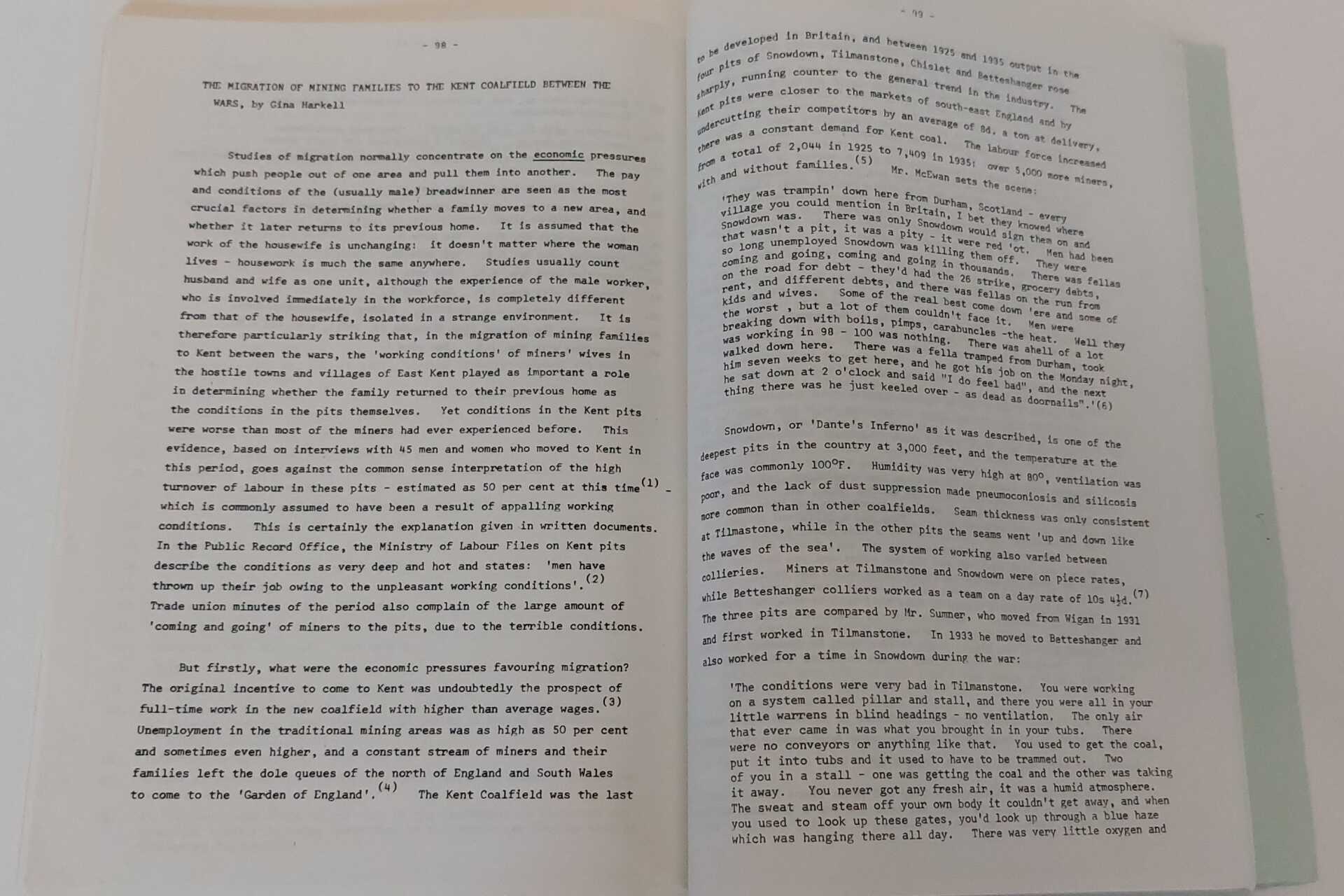

In 1975, Gina Harkell, an undergraduate student at the University of Kent and later an Oral Historian, carried out research into the migration of mining families and what it was like in Kent for both the miners and the miner’s wives. Kent’s mines were known for their harsh conditions when mining at depth, but Harkell found that mining families also had a difficult time adjusting to living in the Kent community.

The Kent residents did not react well to the influx of miners and many

miners, and their families, found that they were treated poorly by residents of

Deal and Dover.

Listen here to a recording of one of Gina Harkell’s oral history interviewees as they describe challenges like renting rooms – where sometimes adverts stated “No miners, No dogs, No children”.

The man at the top of the mineshaft who was responsible for ensuring the cage was safe to descend into the shaft.

Metal tags issued to miners with their own individual number. These were taken in at the pithead so that there was a clear record of who was down in the mine at any time.

The place inside the mine where the coal is cut from the rock

A region rich in coal deposits

A coal miner, or a skilled underground labourer. Other terms for a coal miner include pitman and mineworker.

The entire mining operation on a site –

including all the infrastructure such as offices, other buildings, and often

several pit shafts.

A group of people who stand outside a workplace to protest or to try to prevent people from entering that place of work. A flying picket is a mobile type of picket where picketing workers move from one place to another.

An individual shaft in a mine

The top of a mining pit or pit shaft

A particular bed or vein of coal or other minerals under the ground that has the potential to be economical in terms of production.

A vertical or inclined opening in the ground, made to find or mine ore or other minerals

A snack eaten in the mine, or the name for a 20 minute break taken by a miner

The refusal to work, usually organised by a body of employees, as a form of protest enacted to gain concessions from an employer such as a pay increase of improvements to working conditions

Someone who crosses a picket line during a strike, a strike-breaker. Often used as an insult or a pejorative term.

General term for a hit or a blow with an axe, pick of hammer

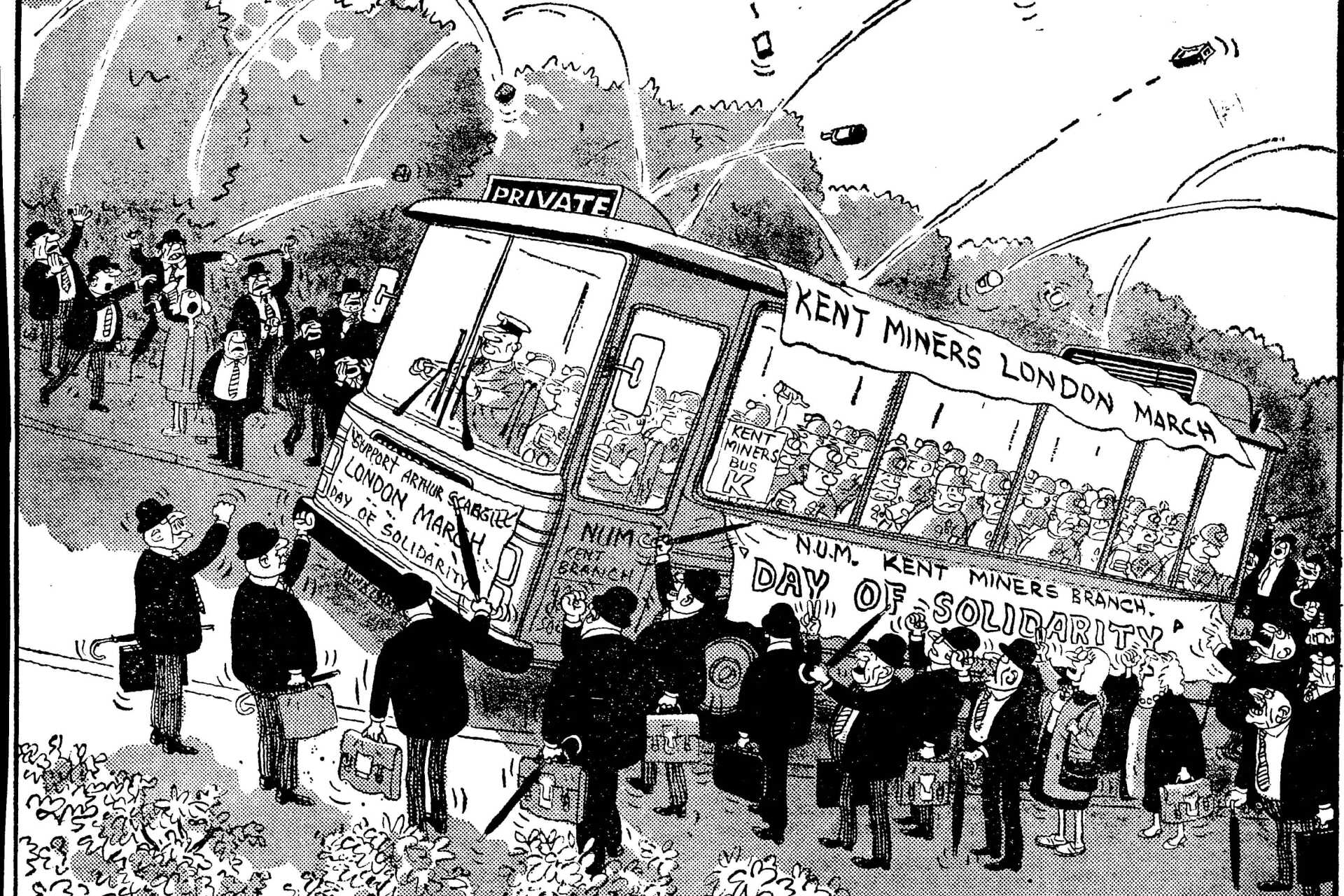

Kent miners were early supporters of the national miner’s strike. Pickets were held across Kent and Kent miners often joined marches in London and elsewhere to protest about the closure of mines and the destruction of mining communities. Throughout 1984 there were regular musical events, fundraisers and rallies in support of strikers and their families.

On March 3rd 1985, while the national strike was announced to be over, the Kent miners remained on strike until it became impossible to sustain, and miners went back to work on 11th March 1985.